Original author: Kaori, Sleepy.txt

Original editor: Sleepy.txt

Meta (then called Facebook)'s creation of stablecoins was never intended to contribute to Web 3.

It was a vision more akin to a central bank and the IMF, enshrined in the white paper from the outset. In 2019, Libra emerged as a global experiment led by a tech giant to create a "digital alternative to the dollar." The Libra Association, headquartered in Switzerland, pegged its currency to a basket of fiat currencies and supported by a comprehensive governance structure and reserve model. The white paper was replete with IMF-inspired concepts.

Before regulators had time to react, Congress had already sounded the alarm for Libra.

Just three days after the white paper was released, Maxine Waters, chairwoman of the House Financial Services Committee, initiated a public hearing, directly pointing out that Libra has financial ambitions to "circumvent sovereignty."

In the three years that followed, Zuckerberg was summoned to testify four times; the token model was changed from a multi-currency anchor to a single US dollar, and sensitive words such as "inclusive finance" were deleted; the partner banks went from running into obstacles everywhere to finally successfully joining hands with Silvergate, and the white paper was also revised from 1.0 to 2.0, gradually compromising with reality.

Meta retreated all the way, but the more it retreated, the clearer it became to the outside world where it wanted to advance.

In January 2022, all of Diem's assets were sold to Silvergate for $200 million, marking the end of the project. Since then, no American tech company has dared to publicly discuss issuing a stablecoin, and Libra has become a symbol of "overthinking."

The coin issuance drama did not end hastily. Instead, it seemed like a case study written by the regulatory authorities themselves, specifically used to draw a clear line for Big Tech.

From the series of congressional hearings to the complete blockade of the bank clearing network; from the refusal to cooperate by channels such as SWIFT and Visa to the withdrawal of alliance members such as PayPal and Stripe; from the internal disagreements between the wallet team and the Libra Association to the official implementation of the "GENIUS Act", not only does the legislation explicitly prohibit platform-type companies from issuing assets anchored to fiat currency, but it also repeatedly names Diem in the law as a "counterexample that must not happen again."

Diem was nailed into history, and a lesson was also nailed into Meta's mind.

Three years later, Meta changed the script

Meta in 2025 no longer seems to be obsessed with issuing its own dollar, but its script has never left the stablecoin track.

Earlier this year, a key figure in Meta's history reappeared within the organization: Ginger Baker was appointed Vice President of Payments Products. This veteran, who has worked at Ripple, Plaid, and Square for many years and is well-versed in compliance, had previously led the development of Facebook's payment system back in 2016.

While Libra hadn't yet been publicly released, the team was already building an on-chain payment prototype. Her track record shows she's been involved in nearly every key regulatory interface. Her return was seen by the industry as a clear signal that Meta was preparing to re-enter the stablecoin market in a different way.

This time, it chose to start with a small incision. Instead of trying to rebuild the monetary system all at once, it started with the payment scenario that is easiest to control and scale up.

According to an exclusive report from Fortune magazine, Meta is in preliminary contact with several crypto infrastructure companies to explore the use of stablecoins as a payment solution—particularly for content creators on its platforms, including Facebook and WhatsApp. Meta is reportedly interested in supporting multiple stablecoins, including USDC and USDT, rather than relying on a single issuer.

In this mechanism, Meta doesn't intervene in the reserve and settlement stages, solely responsible for arranging payment paths between content and the account system. However, structurally, it still firmly controls three key entry points into the financial system: who has the right to receive payments, where the funds come from, and how accounts are settled.

Soon, this trend once again attracted the attention of regulators.

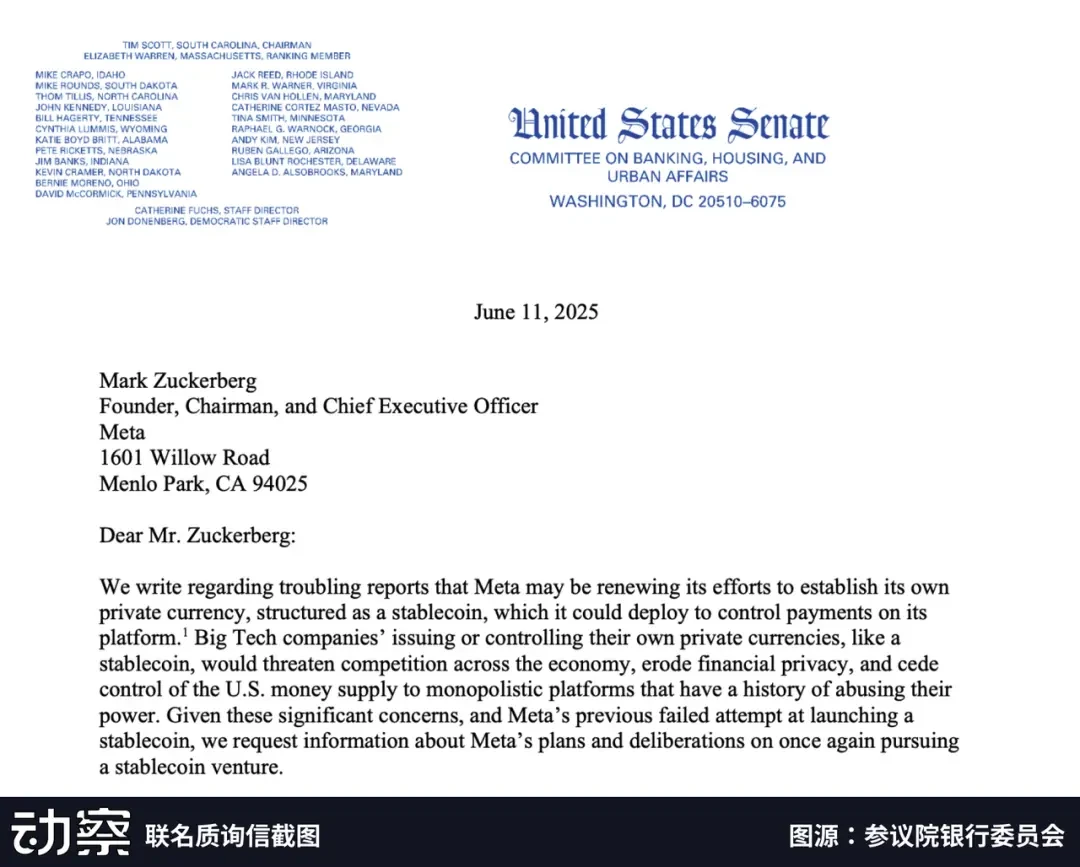

In June of this year, US Senators Elizabeth Warren and Richard Blumenthal sent a joint letter to Zuckerberg, demanding clarification on whether Meta was using the guise of collaboration as a pretext to relaunch a "private currency network." The letter highlighted a crucial point: even if Meta doesn't directly issue a stablecoin, as long as it maintains control over accounts and clearing channels, systemic risks remain.

This series of actions may seem scattered, but the rhythm of each is almost seamless. From the return of Ginger Baker, to the exploration of product mechanisms, and then to the re-registration of regulatory radar, these three seemingly unrelated paths of people, products, and politics ultimately converged in Meta, forming its roadmap for re-entering the stablecoin market.

Meta, which cannot issue stablecoins, may want to make money through "distribution"

The biggest difference between Meta's new path and the Diem era is that it is no longer obsessed with "issuing a stablecoin by itself", but turns to distributing ready-made compliant currencies.

Back then, Libra's ambition was to build a complete closed loop from the underlying public blockchain to the front-end wallet, controlling every aspect of crypto payments. However, this structure came to a dismal end amid regulatory scrutiny before it even launched.

Today, Meta uses USDC as a ready-made dollar settlement module, embedding it into the platform's existing account system, handing over clearing and reserves to a third party, and retaining only the two most familiar positions: traffic aggregation and account system.

In the Diem era, Meta hopes to lock in the right to mint coins through its own stablecoins, recover the minting tax, and charge network fees through clearing channels after cross-border payments are scaled up.

This heavy model was completely blocked after the implementation of the GENIUS Act - the bill prohibits large platforms from directly issuing stablecoins, and requires issuers to have bank-level qualifications and reserve audit mechanisms.

Dante Disparte, Circle’s chief strategy officer, said in a podcast: “There’s a provision in the GENIUS Act that I like to call the ‘Libra clause’ — it’s for the history books.” The provision states that if any non-bank institution wants to issue a token pegged to the US dollar, it must set up an independent entity that is “more like Circle and less like a bank,” pass antitrust review, and be approved by a special committee established by the Treasury Department with veto power.

Disparte believes that this architecture is even "more conservative than the deposit token model proposed by JPMorgan Chase and others."

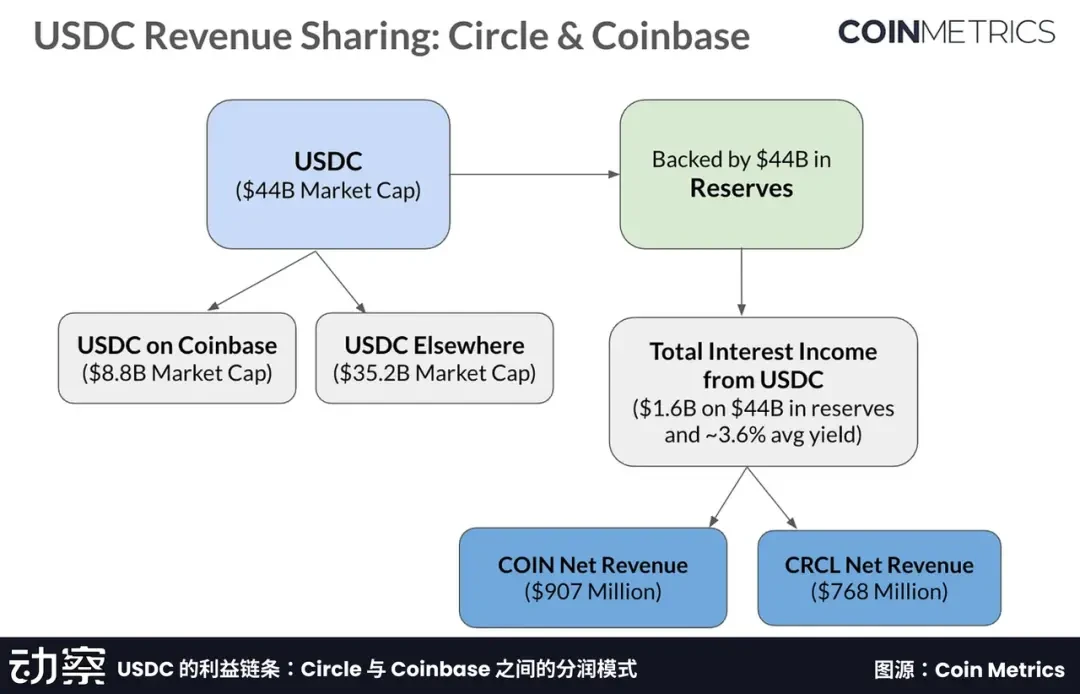

This shifted Meta from being an issuer to a distributor. Meta then partnered with Circle to embed USDC into its account system, with clearing and reserves managed by Circle. Just as Coinbase leveraged its dominant traffic volume to negotiate interest-sharing agreements with Circle, Meta also has the opportunity to leverage its traffic into a new form of financial bargaining chip.

Compared with the long and uncertain minting income, the profit sharing on this settlement path is both compliant and can be immediately included in revenue, which is obviously more realistic.

This role change resulted in a reduction in the size of the technology stack. USDC's issuer now manages the blockchain layer and reserve management, leaving Meta with only user-related modules: account systems, identity verification, and payment routing.

Compliance responsibilities were naturally transferred to the other party, and regulatory pressure was also relieved. Meta refocused its attention on the more familiar aspects of the platform system: account relationships, social chains, and the smoothness of a single payment.

Meta also adopted a completely different revenue model. In the Diem era, it focused on inclusive finance, hoping to expand its market share first and then find profit margins from transfers and exchange rate differences.

Now it is entering the micropayment scenario of the creator economy. Reports indicate that this path can compress the settlement cycle from "month" to "day", greatly alleviating the cash flow friction of cross-border creators.

If this path succeeds, Meta will not only be able to negotiate terms with Circle on channel fees, but also leverage transaction data for targeted advertising and value-added financial services. This "light investment, fast settlement, and strong accumulation" approach is more aligned with the profitability of internet platforms than the previously heavy-handed approach of "building your own central bank."

But regulatory vigilance has not dissipated.

In their joint letter, the two senators pointed out that even if Meta no longer issues its own stablecoin, once it bypasses supervision through a subsidiary structure, its control over the three key links of accounts, payment portals, and data may still bring systemic financial risks and privacy concerns.

Although Meta currently claims to only use USDC as a settlement tool rather than issuing its own stablecoin, the focus of supervision is no longer limited to "who issues the stablecoin" but has begun to extend to "who controls the account and who leads the liquidation."

In this regard, Meta, Stripe, and PayPal are on the same path. They are all trying to hide stablecoins beneath the Web 2 business chain, integrating them into the experience as tools rather than exposing them as assets on the front end.

When money begins to flow on social platforms like pictures and voice, the real competition will no longer be "who issues the stablecoin", but who controls the flow and rhythm of funds.

Stablecoins are taking a backseat

Meta's shift in role is not an isolated case, but part of a larger structural shift.

The passage of the GENIUS Act has drawn fine lines for the issuance of stablecoins. On the one hand, it establishes a federal regulatory path for licensed issuers for the first time, bringing them under the bank-level review and reserve supervision system. On the other hand, it draws a red line, prohibiting large platforms from issuing stablecoins directly or through affiliated entities, completely blocking the "wild path" of building their own monetary systems.

Since then, the narrative of stablecoins has shifted. Instead of competing for "issuance rights," platforms are now vying for "traffic access points."

At the same time, the role of stablecoins is also being reshaped. They are no longer user-facing assets, but rather a set of clearing modules embedded in the underlying system. Companies like Stripe and Meta are beginning to hide stablecoins within the Web 2 payment process, neither displaying them in the user interface nor requiring users to be aware of their existence.

For users, stablecoins are degenerating into an invisible "settlement API"—plug-and-play, no account required, and T+0 settlement. You don't need to understand why they exist, just like you might never have cared about the TCP/IP protocol, yet still watch videos and send messages every day.

This is precisely the starting point for the restructuring of the payment paradigm. The flow of funds is shifting from a closed, bank-centric network to a platform-led, "interface + clearing" network. A new financial division of labor is beginning to take shape between issuers and entry platforms.

Issuers like Circle and Paxos are responsible for reserve management and on-chain clearing, providing the infrastructure for regulatory integration and transparency. Meanwhile, companies like Meta, Stripe, and PayPal serve as the next generation of channel providers, building account systems, payment scenarios, and user interactions, becoming the starting point for capital flows.

They are like card organizations that don't control reserves, but instead control transaction paths, set entry barriers, and define profit-sharing structures. Under this division of labor, stablecoins are no longer just a monetary experiment for a particular platform, but rather a universal, embeddable, reusable, and composable dollar module.

The real change is not that users begin to understand "Crypto", but that they complete a payment without realizing it.

When stablecoins become completely invisible infrastructure, competition between platforms will return to the fundamental issue - whoever can control the path of capital flow will be able to reap profits, set rules, and determine the interface standards and fee structure of the next generation of payments.

Who is rewriting the definition of finance?

If Diem is Meta's failed attempt to become a "central bank", then turning to USDC is more like it changing its approach and staying close to the core of the financial system.

This time, it did not fight for issuance rights, but returned to its familiar territory. However, it controlled the system that was once divided among the central bank, clearing institutions, and banks - identity verification, fund allocation, and payment routing.

The underlying logic of finance is being rewritten bit by bit by the platform.

The GENIUS Act clearly defines the boundaries: stablecoins can be issued, but you can't issue them yourself. However, it doesn't answer another question: if a platform doesn't issue stablecoins but controls the flow of funds, account creation, and data storage, is it a tool provider or a new generation of clearinghouse?

Meta isn't the only answer. Platforms like Stripe and PayPal are also embedding stablecoins into Web 2 business processes. They're compressing on-chain settlements into backend services, minimizing the presence of "crypto" and leaving only a smoother settlement experience.

When stablecoins truly become platform-level infrastructure, public attention shifts from the question of whether they should be issued to the question of who defines payments. Whoever controls the flow of funds in and out has the power to restructure fee structures, set entry barriers, and even redefine how transactions occur.

This raises new questions. For example, will Circle offer Meta a profit-sharing model similar to Coinbase's? Will the senator's questions trigger a new round of hearings? And once stablecoins truly become embedded in the fabric of Web 2, will regulators still be able to find a place to operate?

The Diem story has come to an end, and Meta's new round of attempts is starting anew in another way. The discussion about the boundary between platforms and finance may have just begun.

-END-

- 核心观点:Meta转向分销稳定币,避开监管限制。

- 关键要素:

- Meta放弃自建稳定币,转向支持USDC等合规币种。

- 监管通过《GENIUS Act》禁止平台发行稳定币。

- Meta控制支付路径,仍存系统性风险。

- 市场影响:稳定币竞争转向流量端口控制。

- 时效性标注:中期影响。